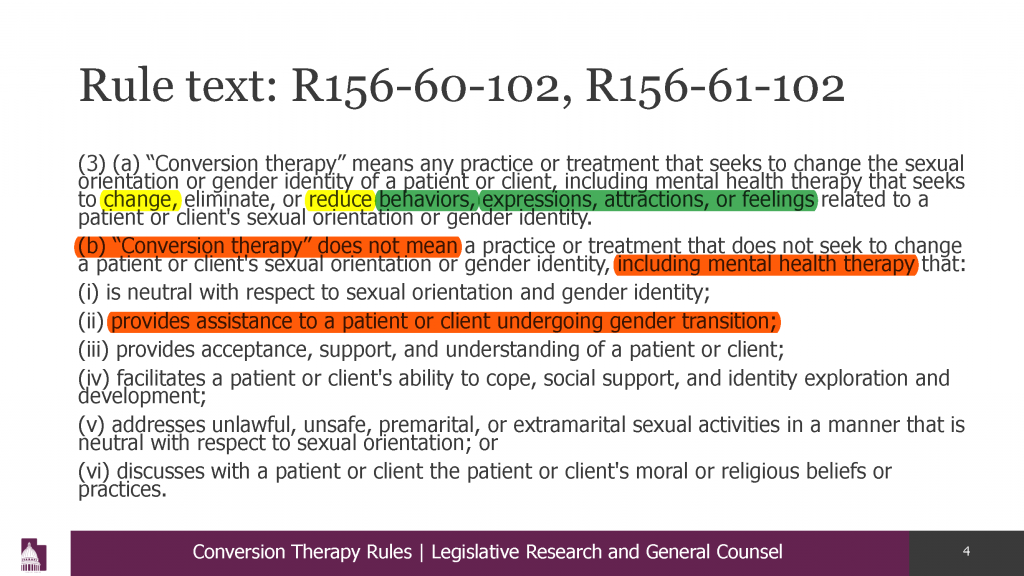

A recent article in the Salt Lake Tribune unclearly characterized my comments to the Utah State Legislature on August 18 regarding conversion therapy. I would like to clarify them. While I oppose the current version of the conversion therapy rule, I do not support conversion therapy. As a therapist, I don’t believe changing sexual orientation is an appropriate goal in therapy. But I oppose the conversion therapy rule because not only does it forbid these kinds of attempts to change sexual orientation, but also brands a much broader range of interventions as “conversion therapy,” including assisting clients who wish to manage their sexual behaviors.

There are many who find certain sexual behaviors incongruent with their values, and that should not deny them access to mental health care. So the rule is too broad.

But the rule is also too narrow because it does not protect young people from unethical gay affirmative therapists who express religious bigotry and limit their clients’ options for integrating their sexuality with the rest of their identity. Young clients have been harmed by therapists doing these things. Why do they matter less than other victims?

There is another form of conversion therapy happening to young people right now, under everyone’s noses, and this is where my testimony about puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones could be misunderstood. We are learning that some young clients would rather be trans and straight than “cisgender” and gay. If past clinical outcome data holds true today, that number could be 70-90% of them. Yet this form of “conversion therapy” is explicitly allowed by the rule. But what happens if therapists foster a more careful exploration process where the client might discover confounding factors that could be feeding gender dysphoria, including confusion and shame about possibly being gay? They risk getting hauled before DOPL, having their reputation trashed, and losing their livelihood. The incentives are not aligned with the potential harms, because the potentially irreversible physical consequences are the ones that are exempt from scrutiny under the rule, while it has been decades since anyone has been subjected to discredited and harmful shock therapy. The rule isn’t calibrated to today’s risks.

Meanwhile, the rule’s vagueness has scared away clinicians from treating this population. How do I know that? Because clinicians have told me they are, and clients tell me they have a hard time finding therapists who will support their realistic treatment goals. I do not think a rule that results in this vulnerable population getting less care is a good one.

Above all, this rule does not respect client self-determination. In my view, neither the government nor the therapist should dictate the goals of therapy. That should be entirely up to the client.

I believe a more collaborative, inclusive, and less punitive process might result in a solution far better than we have now, which was simply copied from other bans enacted elsewhere. In short, the current rule is incentivizing less care and less helpful care for a population that needs more care and better care. What if we could truly help a lot more vulnerable young people rather than simply fight another battle in the same wearisome culture war? That would be the “Utah way.” I sure wish I could “convert” everyone into trying that!

-Jeff Bennion

Thank you Jeff! This is so well said!