Follow the Prophet is a beloved phrase and a primary song, until it isn’t. And it usually stops being beloved when church members begin to assert their own internal authority:

“I determine my faith commitments”

“The church doesn’t get to dictate to me what I believe”

“I follow Jesus over the church”

“There’s no middle-man between me and God”

“I’m the one who determines what my church participation should look like”

“We’re all cafeteria members, so my choices in the cafeteria are no less valid than someone else’s”

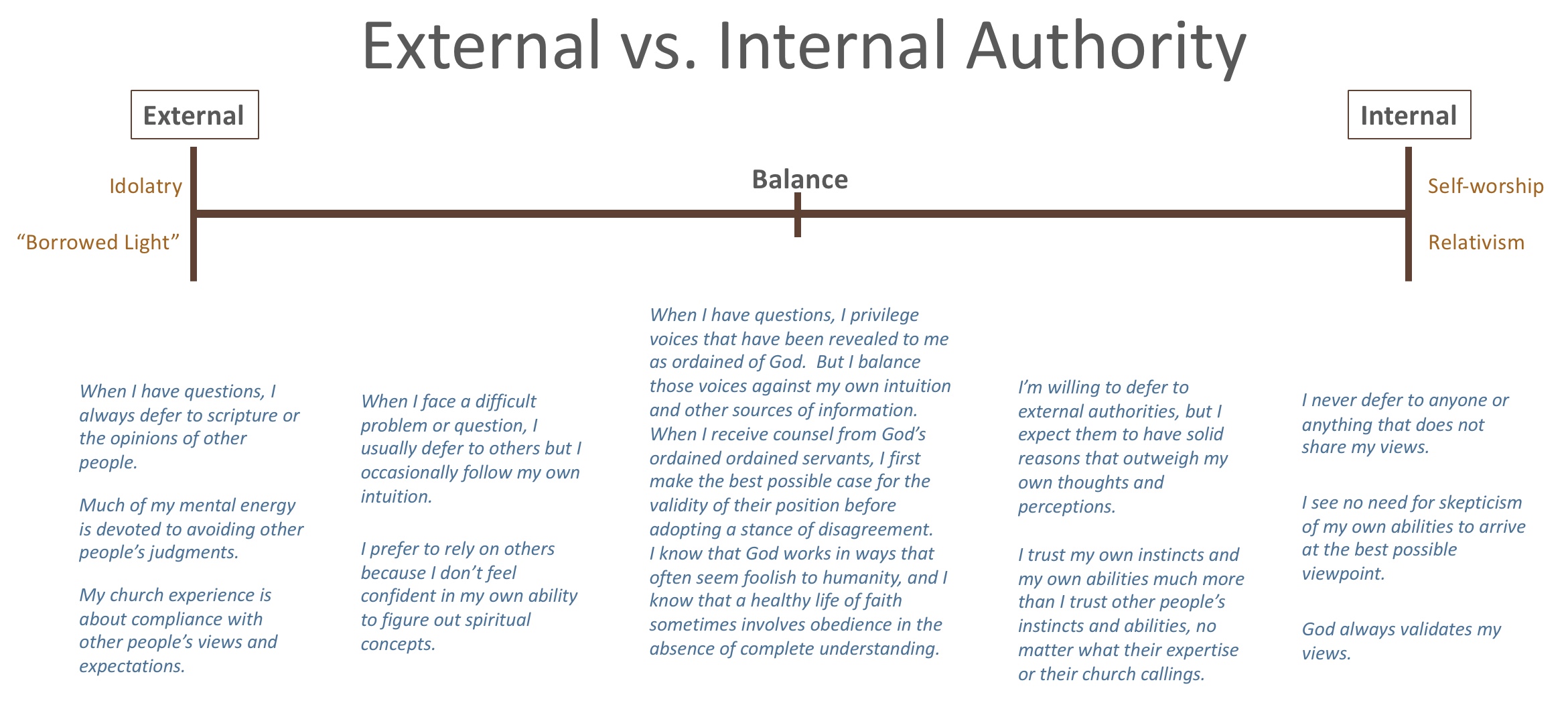

These are all statements of personal authority, and these particular statements are common among people who have grown disillusioned with the church, while remaining members. Part of the normal pattern of belonging to a belief system (religious or otherwise) is to go through a transition from reliance on external authorities, to some exercise of our own internal authority.

As church members going through that developmental transition in our faith, sometimes we tend to assert our internal authority and wear it like a badge of honor. “I’m not like those people who follow the prophet blindly. I’m not a sheep. I’ll never obey something that goes against my views.” This language often reflects cynicism, where someone lives perpetually in a state of fear of being disappointed, and their ability to engage well with people and institutions becomes extremely limited as a result.

On Cynicsm, Chloe Bonini offers the following insight:

Habitual cynicism in others is a learned behavior. Cynicism becomes a habit because that person feels comfortable and safe with a wall up, constantly ready to assume the worst in every person and every situation. They feel safe being able to put themselves in a position to advocate for their own righteousness while they scrutinize the flaws and shortcomings of everything and everyone around them.

Habits are hard to break. They become habits for a reason. Things like habitual cynicism are behaviors people have to want to unlearn, and bringing up this problem to this person will more likely offend them than cause them to examine their behavior.

A cynic will never be fully willing to assume that someone else is correct to be optimistic or positive. A cynic will constantly tell you your optimism is ignorance, and the world doesn’t work like that. A cynic adopts these attitudes because they also take up this rhetoric with themselves. Every failure should have been predicted. Every success pales next to everything that is wrong. A cynic will avoid paying attention to what can work, what will work, or what does work. Cynicism comes from lack of self belief, and if you let it, a cynical person can wear you down.

Sometimes our critics present us with a cynical hypothetical designed to show that our commitment to follow the prophet makes us somehow morally blind: If the prophet told you to murder someone, would you do it? And in fairness, it’s true that people of faith (and atheists too) have sometimes done horrible things in deference to authority figures; the Mountain Meadows Massacre is an example of this in our Latter-day Saint history. But we are not at all obligated to indulge people’s moronic hypotheticals. The odds that President Nelson is going to call me up and tell me to murder someone are ridiculous, so my answer to people who propose this insinuation-question is, give me a hypothetical that is not totally ridiculous, and I might take the time to answer it, if I sense that you are serious about really understanding my point of view. A good principle in these situations is, don’t engage with people who are unserious, and a good indicator of someone’s seriousness is the quality of their hypotheticals.

Returning to the development of our internal authority- never examining and questioning anything that comes from church leadership is one form of immaturity, but developmentally, our tendency is not to step out of that mindset into a mature mindset. Rather, we tend to step into a different form of immaturity: “I’ll follow the prophet, but only on my own terms.”

As an analogy to illustrate this immaturity, think of building a house, and the importance of adhering to building codes. Building codes are rules established by architects and engineers for constructing homes and other buildings, and they evolve over time as our understanding of construction and engineering improve. Imagine if I were to go into the office of a local county building inspector and say “I’m going to build a home, and I’m going to build it according to my building codes.” The conversation might proceed as follows:

Inspector: What are your building codes?

Me: Well, I only really have one building code that I follow. My building code is love.

Inspector: Wow, you must be an amazing person, at least in your own estimation. Does your building code of love result in structural integrity for walls and roofs and foundations and other elements of a building?

Me: I don’t think structural integrity is important as long as people in the building feel loved.

Inspector: Okay, it sounds like you wish to live in a tent, and we do have campgrounds in our county where you can live in a tent as much as you like. But if you plan to build an actual structure according to your building code of love, you will need to do that in another county, one where people’s actual well-being is defined as something more than a pleasant feeling. This county has laws that reflect a belief that it’s not loving to put someone in danger, in a structure that will collapse on them.

Me: Okay, I still want to build in this county. But I don’t like your building codes.

Inspector: That’s fine, but we will still require that you adhere to them. And if you want to pout and stomp your feet and whine about them, that’s clearly a maturity issue on your part. But there is another option: you can file a request for an exception to code.

Me: I can create exceptions to the building codes?

Inspector: Sure. All you need to do is research the engineering behind your proposed exception, document how it will maintain structural integrity, and provide examples of how your exception has been successfully implemented in other buildings.

Me: But that involves work.

Inspector: I know, and your building code of love doesn’t. But if you’re serious about building here in this county, that will involve work on your part. Welcome to adulthood.

Reading this imaginary exchange, you might be inclined to respond so the point of living the gospel is just to maintain compliance? And the answer is emphatically no. Extending the analogy, the point of the gospel is not to forever live on borrowed light, deferring to other people’s understanding of building codes. The point of the gospel is to become a structural engineer who personally understands and sees the value of building codes. In gospel terms it means developing wisdom, which is a really difficult lifelong process of learning how things work; why some ideas are sound and others are not; which ideas are almost-good but harmful; why some things are more relevant and important than others; when it makes sense to defer to external authorities over our own perceptions; and more. Developing wisdom is a lot of work. It’s a lifelong process, and often a painful one that leaves us with scars. But people who are genuinely wise are, in scriptural terms, mighty. They are the closest thing we have to actual superheroes.

And now you might have another question: is it okay to disagree with prophets? Is it okay to disagree with church leaders’ teachings, and disagree with policies? And the answer is emphatically yes. If you find yourself in that situation of disagreement, it does not mean you are unfaithful or a bad person. It just means there is work to be done, so welcome to adulthood.

And what is that work?

- Accounting for my own biases and worldview as I approach questions and issues

- Adopting a good set of cognitive ground rules

- Exploring the best possible case for the validity of the church’s teachings and policies. Do I even have an accurate understanding of the engineering behind our current building codes, so to speak?

- Being open to revising my own views if needed (basic humility)

- Examine honestly whether changes I envision for the church have already been tried in other places, and what the impacts have been.

On that last point, I have progressive-leaning friends in the church who are hoping that the church will embrace the “building codes of love” that were embraced decades ago in mainline Christianity: women’s ordination, LGBT affirming, low view of scripture, doctrinal relativism, and so forth, all in the name of “inclusion.” What has been the effect of those changes in those denominations? Was it more “inclusion?”

To honestly reckon with the real-world effects of our ideas is difficult, and it requires maturity. Welcome to adulthood.

When we reflexively reject the church’s teachings and policies without doing any real work to understand the value of those teachings and policies, or understand the real tradeoffs involved in different courses of action, we might think that our rejection is an expression of our internal authority. And yeah, technically it is. But developmentally it’s on the same level as the toddler who is super proud of his newfound mind-blowing realization that he has autonomy, and he can use that autonomy to take off his diaper.

Congratulations, little Billy, on your amazing internal authority.

So you’ve come to the realization that you have internal authority, that you have a choice in whether or not to follow the prophet, that you have the ability to accept or reject church teachings? Fantastic. Developmentally, that is an important step for you. Now you have choices to make, either in the direction of spiritual adulthood (self-awareness, study, honest weighing of tradeoffs) or perpetual spiritual childhood (murmuring, whining, pouting, demanding).

So in conclusion, “Follow the prophet” is not at all an expression of immaturity or naivete. For many Latter-day Saints it is a commitment that comes from a place of deep wisdom acquired through honest searching and examination and self-awareness that our critics cannot relate to because developmentally, like the toddler celebrating his lack of a diaper, they have never acquired those mental and spiritual muscles. And let’s be clear- it’s okay to not have those muscles, especially if you are young and just learning how to navigate life and the world. But if I lack the maturity to envision “follow the prophet” in any terms other than blind obedience, I would do well to avoid projecting that false, narrow, binary thinking onto people who are more methodical and informed in how they approach their faith commitments.